The new speed boat is coming together sweetly:

It will be 20′ long by 7’6″ weighing about 2100 pounds, and capable of carrying 8-10 people. This will be powered by an outboard motor of 150-200 Horse Power to push the boat to perhaps 45 MPH. At 450 pounds, the outboard delivers a much better power to weight ratio, and sitting right there on the transom, makes for easier maintenance. An old Mercury 200 Tower of Power like the one below would be the perfect attitude, but then, there goes the ease of maintenance.

The new wooden speedboat will follow a similar construction plan as the first, built of wooden cross-frames and stringers. This time, however, I plan to use a more local variety of wood, starting with the lumber left on my racks from a decade plus of projects. This will include some White Oak, Alaska Yellow Cedar, some Mahogany. These are from long and straight boards, with no knots, and rot resistant.

But my 10-12′ American Cherry lumber is also great to work with, and can be sized appropriately for the strength and function needed. Building a hull stiffened by fiberglass cloth, embedded in epoxy to keep the water out, is a far more important factor than the wood type.

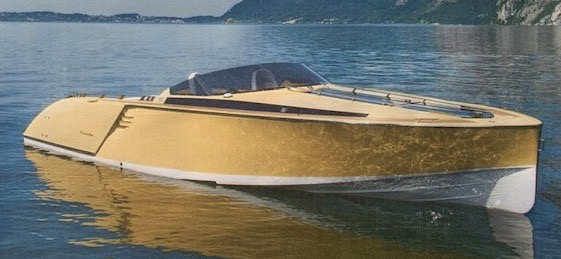

The design concept has firmed up as well, taking inspiration from boats like the Frauscher below.

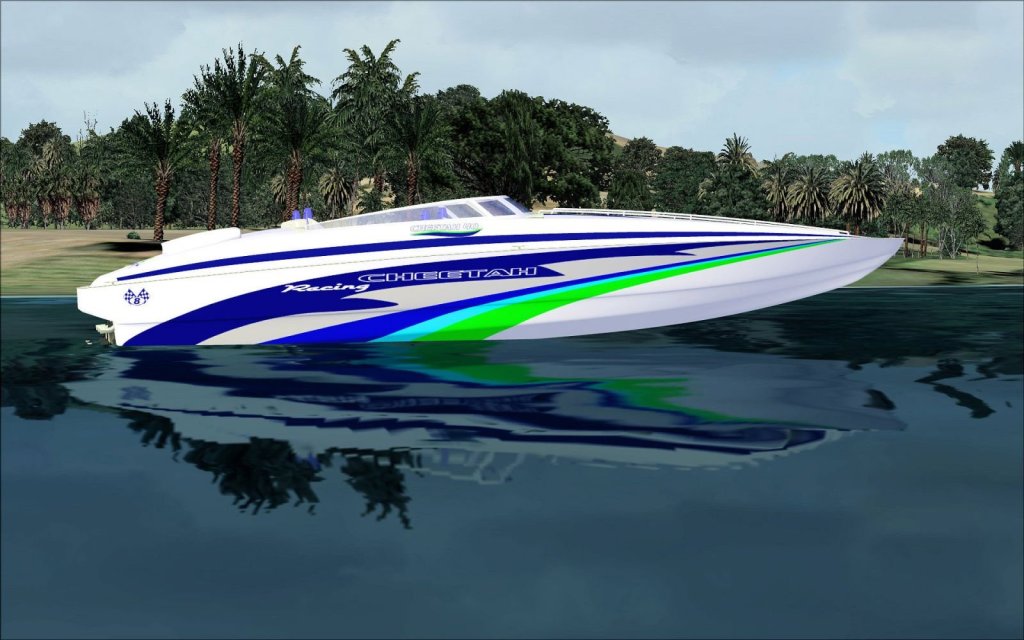

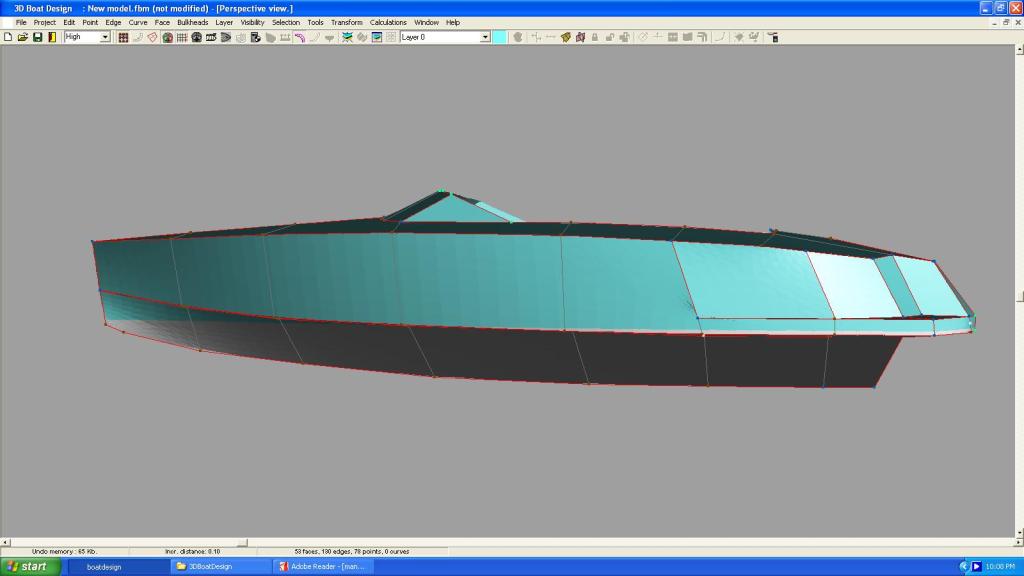

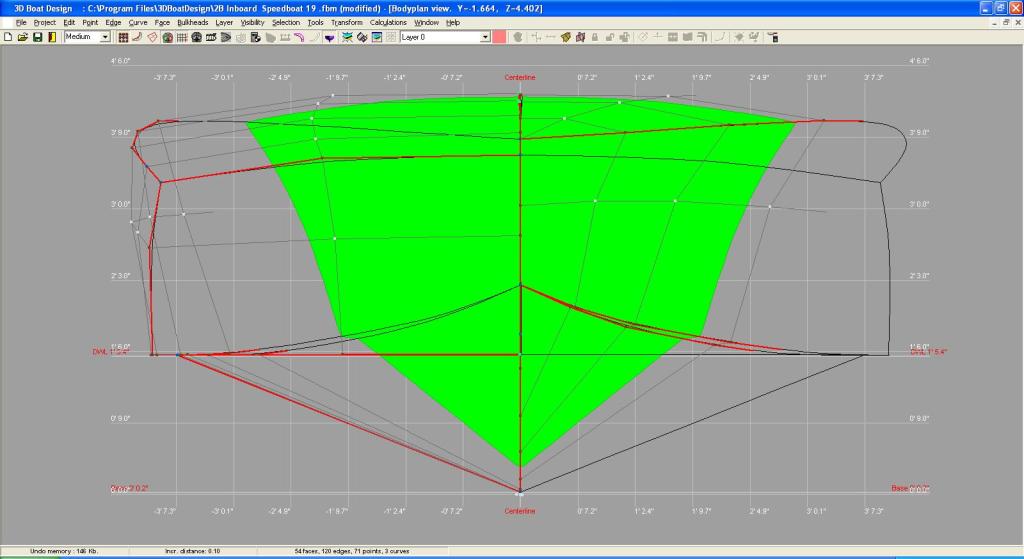

Some examples of work from my design program are shown below. This is not exactly the boat I am building, but it shows what fun a fairly simple program can create.

The boat shown below is also not the exact model I used for the frames. It does however, show a more vertical bow line, and forward leaning transom above the waterline.

The first serious step towards production was making a series of PDFs of the bulkheads from my boat design. Below is cross frame number 6, third from the front. My old computer with the free boat design program is 25 years old, and with my lack of tech savvy, I hoped that it could still be used.

One day I came to the moment of truth. Was this to be only a design hobby or am I actually going to build a boat? I called Tyler at Cutting Edge CNC in Millersburg, Indiana to ask if he could use the PDF’s. He said that it was quite possible and he would give it a try. In few days later, he said bring the wood!

For the last boat, (frames shown on right), I used large patterns and assembled all of the frames from Alaska Cedar and Marine Plywood parts.

This time I am trying a different approach, having the frames cut from 4 x 8 sheets of Hydrotek plywood. Then I will reinforce them later.

At Johnson’s Workbench in Charlotte, Michigan, I bought the 6 sheets of plywood, and dropped them off to Cutting Edge. Another couple of weeks, and voila’ the possibility of a boat became real!

After I received the cross frames, I went back to my computer design program to review the actual model’s side view lines. This was for the final information about how to position the bulkheads vertically, especially the front 3 or 4.

With apparent careless habits from new computers, I did not press save one time, and experienced the unfortunate disaster of the old days of computing. The current design concept was not shown above. . . because it is gone.

None of my efforts, or advice from experts to recover the design worked, and there I lost many hours of irreplaceable work. There is a lot about building boats that is like life.

Till next time . . .