Boat strength is an imperative topic in the creation of a boat, designed to safely carry people. If you want the full story in mathematical detail, Dave Gerr wrote a book called The Elements of Boat Strength for Builders, Designers, and Owners. You could call him “Noah Thing or Two.”

He lays out multiple graphs of plank and frame dimensions for all sizes of boats. This gave me comfort on the first boat when I planned the shell thickness of 1/2″ on the side and 3/4″ on the bottom. When I covered it inside and out with fiberglass fabric embedded in epoxy, I figured it was all good. So far it has survived lots of railroad crossings which will show up the weakest link.

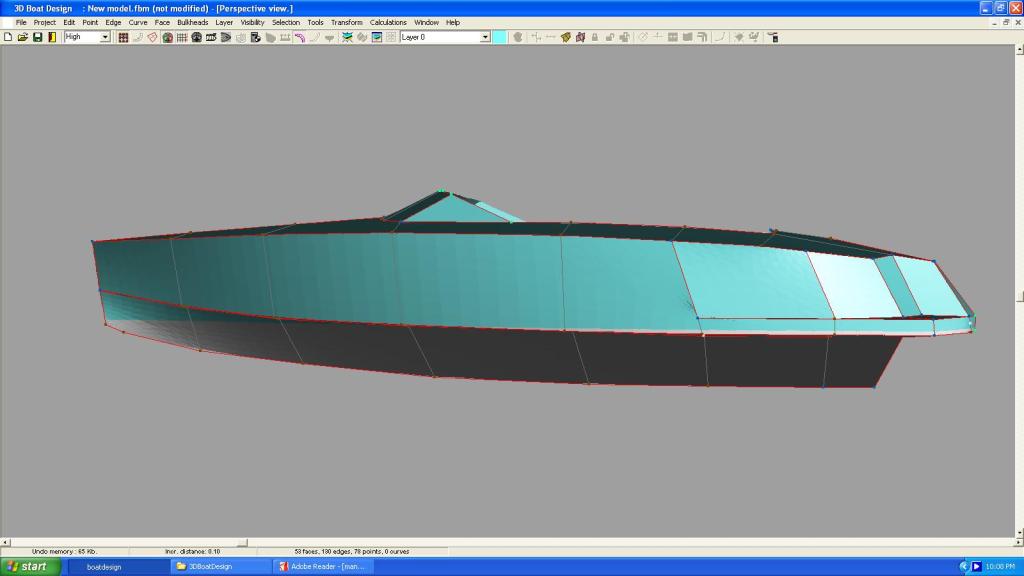

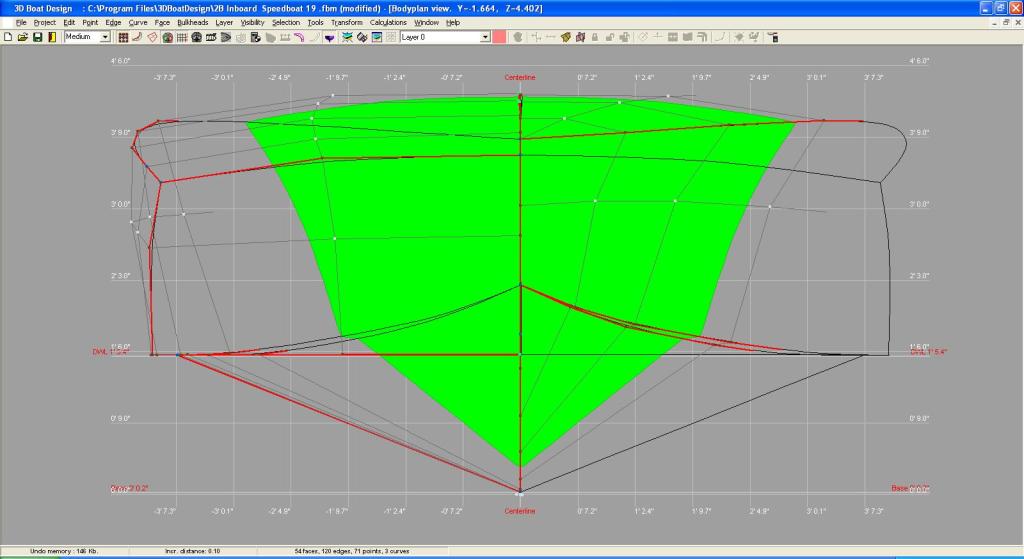

Since I started with the 1/2″ Marine plywood, CNC cut cross frames, I needed to first strengthen them.

The Alaska Yellow Cedar left over from the first boat served admirably to stiffen the edges and provide general frame strength. The deck will be reinforced after turning it over.

Next, the frames needed to be connected, and the keel was the first place to start. The fair curve of the line was more critical than strength at first, so I used a single piece of Cherry that was planed down just thin enough to make the bend without needing to do any steaming. Ah the beauty of the line, however weakly drawn!

Then I added thicker wood under the long keel in proportion to what strength might be needed at each area. The boat is upside down right now, so the upper left corner of the boat is going to be the lower front of the hull when it is done.

The triangle corner brace is a three piece lamination of marine plywood. Of all corners of the boat to take a hit, on a rock, the sand, a log or a dock, this is the likely place where the most damage would be done.

Across the top of the single board that created the keel line, I laminated a second board to give it more stiffness. The back 8 feet are straight, for consistent planing.

Internally, the long boards were added to tie it all together, define the space for the fuel tank, and to pass the force of the future motor to the boat as a whole.

This is a wider boat than the first one I built, and it seemed like it could use a second long runner, to help stiffen the shell. I sawed and chiseled out some notches on the frames and runners to retain the best strength on both parts.

Someday it will sit for long periods of time on a trailer. The outer runner is about where the trailer bed rail will hold it, which can deform the hull if it is not strong enough.

A finely curved laminated stringer at the chine line (where the bottom meets the side) will be the remaining connector before the hull planks go on . . .