The physics and math of fluid flow across a hard surface is pretty complicated, but taking a common sense approach can bring a good bit of direction to a new boat design. The first main decision is whether the boat is supposed to go slow or fast.

Slow, displacement boats when moving, stay nearly at the same depth as a rest. Speed limits are defined mostly by the length of the object, and the length-to-width ratio. The row boat below is beauty in motion, although quite slow.

This God designed hulk of a whale is a far more efficient displacement machine. Even though it has to push its full girth through the water, It has a super slick motion, with speeds exceeding 20 mph for short distances.

Wood boats can’t begin to replicate all the whale’s body mechanics of flex and fin stroking. But, human engineers have done some of their most successful design work, imitating performance seen in nature.

Another group of boats are called semi-displacement, for their ability to go efficiently at a slow cruise, and still go beyond displacement speed with more power. Generally, the more pointed the front, the less effort to go forward. A catamaran uses two hull halves to make even narrower parts, with sharper entries.

At the back of the boat, the deeper it sits, the more wake it produces, and the less efficient the power-to-speed ratio. Below is a fine design of a semi-displacement hull. The front of the hull is a cutting edge; the water flows to the side and under the boat. By the time it gets to the transom, the water returns almost up to the original water line. That leaves very little turbulence, or wake drag.

But that’s all academic if you want the boat to go fast, with grab rails! Fast boats are designed to ride on top of the water, and have to be powered strong enough to push the hull up on plane. Then the water touches a much smaller friction pad, generally the back half the bottom or even less.

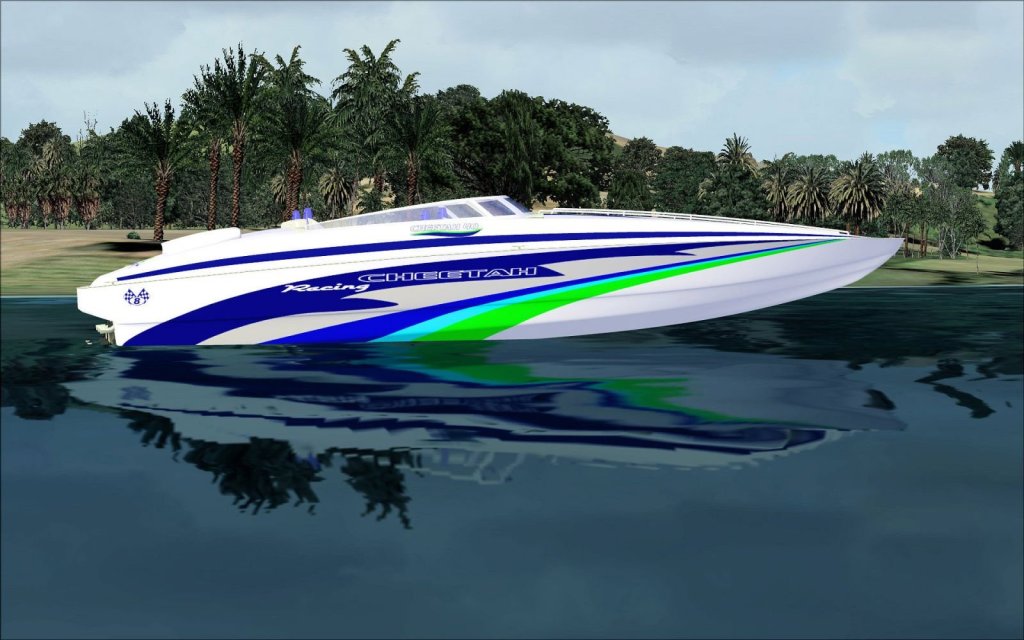

The contact area is smallest on a flat bottom like some of the old traditional woodies, but that gives the most pounding ride on choppy water. Ocean racers like the beauty below use a steeper dead rise angle from the bottom to the side, up to 24 degrees, giving a more stable and comfortable ride for aggressive wave hopping. By the time they power up their twin 450’s, they may have only the back third of the boat hitting water, some going over 100 mph.

Principle 1 of intuitive design: Define your speed goals and imitate success! I have reinvented the wheel enough times to realize a bike really cannot steer from the back tire, for example.

Principle 2: slow boats are usually wider to their length, and fast boats get narrower. The ocean racers generally are at least 3:1 length to width. My first boat was 20 ft. long and 6.5 ft. wide for a slightly more than 3:1. However, for a smaller boat, it gives up some lateral stability, and overall carrying capacity. The new boat will be 20 ft. to 7.6 ft wide or 2.6:1. This will provide the extra buoyancy for a few more grand kids to jump on.

Principle 3: the dead rise angle. The Raveau Racer above, built by Bob Walwork, has a flatter bottom angle. It is a single purpose boat, run mostly in calm water, as the Raveau drivers tend to be addicted to speed.

For my boat, I have narrowed down to a more general purpose speed boat, with 20 degrees dead rise, which seems to be a pretty good mix of a comfortable ride on flat water or some more choppy conditions. it is some guess work, but some things in life don’t have mathematical answers.

If you look at the bold black outline, you can see slight tip in at the transom, or stern. This “tumble home” is a consistent characteristic that will make it feel comfortable around the old classics. Nearer the middle of the boat, the green Number 3 cross frame, shows that the outside of the hull has a slight outer tip. The light lines show this tip out angle increases more towards the front of the boat, to keep water spray out.

Do a little research, weigh the options, try to evaluate the pros and cons, and then there comes a moment of decision.

More to come. . .